Not enough time to read the full article? Listen to the summary in 2 minutes.

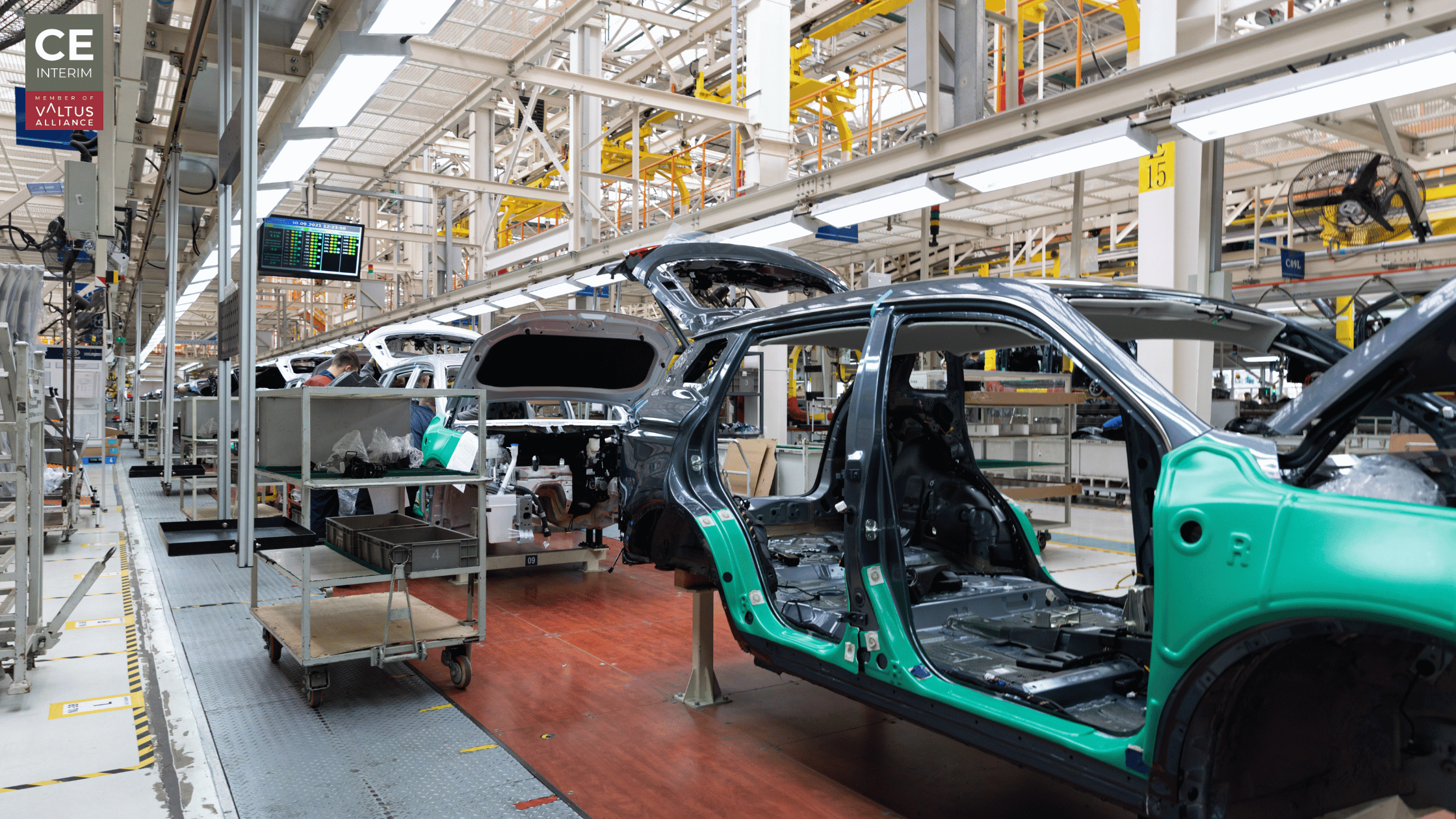

In February 2025, Saudi Arabia formally designated the King Salman Automotive Cluster in King Abdullah Economic City as a national automotive manufacturing hub. The intent is clear.

Build a concentrated ecosystem that brings together OEM assembly, supplier development, logistics access and export capability under one coordinated industrial platform.

The anchor names are already visible. Lucid began operations at its AMP-2 facility in KAEC in 2023, with phased capacity plans that extend well beyond initial volumes.

Hyundai Motor, through its joint venture with PIF, broke ground in 2025 on a plant targeting 50,000 vehicles annually, with first production expected in the second half of 2026. Ceer, Saudi Arabia’s domestic EV brand, secured more than one million square metres in KAEC’s Industrial Valley for its manufacturing base.

Public reporting frames the cluster as capable of attracting three to four major manufacturers and eventually exceeding 300,000 vehicles per year. The projected GDP contribution is measured in tens of billions of riyals by 2035.

The ambition is real. The infrastructure is visible. The capital is committed.

But automotive manufacturing is not judged by square metres or announcements. It is judged by stability at volume.

Capacity Is Not the Same as Run at Rate

In automotive, “run at rate” has a specific meaning. It is not the first unit off the line, the ribbon cutting or the successful validation build.

Run at rate means:

- Stable daily output at committed volumes

- Predictable yield and scrap within design assumptions

- OEE that does not oscillate unpredictably

- Inbound material arriving without chronic expediting

- Maintenance routines preventing volatility rather than reacting to it

- Logistics and port flows synchronized with production cadence

Construction risk is visible and finite. Ramp-up risk is subtle and systemic. Many plants complete construction on time. Fewer achieve stable output within the first 90 to 120 days without friction.

For a cluster launching multiple facilities in parallel, this distinction matters.

Parallel Ramp-Ups Multiply Execution Risk

Lucid is expanding in phases. Hyundai is targeting SOP in 2026. Ceer is building a large footprint with national visibility. These are not isolated assets. They are co-located within the same industrial ecosystem, drawing from overlapping talent pools and supplier bases.

Parallel ramp-ups create predictable pressures:

- Competition for experienced production supervisors and maintenance leaders

- Accelerated promotion of middle managers before they are fully seasoned

- Shared local suppliers stretched across multiple OEM requirements

- Increased demand on logistics infrastructure and port coordination

The first 90 days of production rarely resemble the clean curves presented in board decks. Yield learning takes time. Maintenance stability takes discipline. Supplier qualification takes repetition.

When three or four manufacturers are stabilising simultaneously, small weaknesses in leadership density or supplier readiness are amplified.

JV Governance and Decision Rights Under Pressure

The Hyundai manufacturing entity in KAEC is structured as a joint venture, with a 70 percent stake held by PIF and 30 percent by Hyundai. Such structures are designed to combine global technical capability with national industrial strategy.

They also introduce governance complexity.

Automotive plants operate on hourly problem resolution cycles. Boards and shareholders operate on quarterly oversight rhythms. If decision rights are not clearly defined, friction emerges at predictable points:

- Specification changes requiring cross-entity approval

- Capex adjustments during ramp-up

- KPI definitions differing between global headquarters and local management

- Escalation pathways that are unclear in real time

In a steady-state plant, governance friction can be absorbed. In a ramp-up environment, latency translates directly into scrap, missed schedules and cost leakage.

The question is not whether governance exists. It is whether plant-level operating authority is clear enough to support daily industrial decisions.

Supplier Ecosystem and Localisation Physics

An automotive cluster is only as stable as its supplier network. The King Salman Automotive Cluster is designed to strengthen domestic supply chains and reduce import dependency. That objective aligns with national industrial policy.

Operationally, localisation introduces timing risk.

Supplier development requires:

- PPAP and quality validation cycles

- Consistent delivery performance before volume scaling

- Transparent escalation protocols

- Financial resilience in Tier 2 and Tier 3 suppliers

If inbound parts are unstable, the assembly line becomes the shock absorber. Overtime increases. Expediting becomes routine. Inventory buffers expand beyond design assumptions.

Export orientation adds another layer. Documentation accuracy, customs alignment and port scheduling must operate without noise. Automotive customers do not differentiate between cluster ambition and late deliveries.

The early signals of supplier immaturity are subtle:

- Repeated containment actions on the same components

- Emergency freight normalised into the cost structure

- Planning teams manually reconciling data discrepancies

- Line stoppages blamed on “start-up turbulence” long after SOP

These are not structural failures. They are system-building gaps.

The Leadership Density Question

Large industrial programmes often underestimate one variable: the density of capable leaders per square metre.

Buildings can be constructed quickly. Equipment can be installed on schedule. But middle management maturity does not scale at the same speed.

In ramp-up environments, leadership stress shows up in specific ways:

- Supervisors promoted before mastering daily management discipline

- Maintenance teams operating reactively rather than preventively

- Tier meetings inconsistent or poorly escalated

- KPI dashboards present but not trusted

Automotive plants require a tiered management system that runs every shift. Escalation loops must close within hours, not weeks. Root cause analysis must be habitual, not episodic.

In high-velocity industrial expansions globally, boards often deploy interim plant directors or COOs during the stabilisation phase. The objective is not replacement of permanent leadership. It is embedding cadence, clarifying decision rights and transferring capability before handing over to a steady-state structure.

Clusters are not constrained by capital. They are constrained by how quickly leadership density can be built.

The First 120 Days After SOP

The most decisive window in any greenfield automotive plant is the first 120 days after start of production.

This is when:

- Commissioning documentation is tested against real output

- Spare parts strategies reveal whether preventive maintenance is viable

- Training depth is exposed by shift variability

- Quality control plans either prevent or amplify early scrap

- Data systems either support decisions or create noise

Three operator-level disciplines often determine whether ramp-up stabilises or spirals:

1. Clear readiness gates before volume escalation

2. Daily KPI cadence with transparent escalation paths

3. Defined ownership of supplier stabilisation and maintenance routines

When these disciplines are weak, production does not collapse overnight. It erodes through volatility. Output fluctuates. Confidence declines. Investors ask for recovery plans.

When they are strong, yield improves week by week. Variability tightens. OEE trends upward. Supplier issues reduce in frequency and severity.

Run at rate is built, not declared.

The Cluster Will Be Judged by Operating Systems

The King Salman Automotive Cluster represents a significant step in Saudi Arabia’s industrial transformation. The infrastructure, global partnerships and capital commitment are visible and substantial.

Yet automotive history shows that clusters are not ultimately evaluated by their opening ceremonies. They are evaluated by sustained, predictable output.

The decisive question is not whether vehicles can be assembled in KAEC. It is whether multiple plants can achieve and maintain run-at-rate performance under localisation pressure, JV governance complexity and export ambition.

Industrial ecosystems mature when operating systems mature. That requires leadership clarity, supplier discipline and daily management rhythm that withstands volume commitments.

Saudi Arabia has the ambition and the investment. The operational question is more specific.

When volume commitments meet daily industrial reality, who owns the operating system?